In a significant stride towards unlocking the potential of fusion energy, Everett, Washington-based startup Helion announced Friday that its Polaris prototype reactor has successfully achieved plasma temperatures of 150 million degrees Celsius. This monumental accomplishment represents three-quarters of the way towards the company’s target temperature for operating a commercial fusion power plant, marking a pivotal moment in the global race to harness this virtually limitless source of clean energy.

"We’re obviously really excited to be able to get to this place," David Kirtley, Helion’s co-founder and CEO, shared with TechCrunch, his voice reflecting the immense satisfaction and anticipation of this breakthrough. The achievement is not just about reaching a specific temperature; it signifies a deeper understanding and control over the complex processes required for sustained fusion.

Furthermore, Helion revealed that Polaris is now operating with deuterium-tritium fuel, a mixture of two hydrogen isotopes. Kirtley stated that this development makes Helion the first fusion company to achieve this milestone. "We were able to see the fusion power output increase dramatically as expected in the form of heat," he elaborated, underscoring the tangible results of this advanced fuel combination. This ability to effectively utilize deuterium-tritium fuel is a critical step towards demonstrating the viability of fusion as a practical energy source.

The fusion energy sector is currently experiencing an unprecedented surge in investment and innovation, with several companies vying to commercialize this transformative technology. This week alone, Inertia Enterprises announced a staggering $450 million Series A funding round, backed by prominent investors like Bessemer and GV. In January, Type One Energy revealed it was in the process of raising $250 million, following a significant $87 million round. Last summer, Commonwealth Fusion Systems secured an impressive $863 million from a consortium including tech giants Google and Nvidia. Helion itself has been a major player in this funding landscape, raising $425 million last year from a group of high-profile investors such as Sam Altman, Mithril, Lightspeed, and SoftBank. This influx of capital underscores the growing confidence in fusion energy’s potential to revolutionize the global energy infrastructure.

While many fusion startups are targeting the early 2030s for grid-connected power generation, Helion has set an ambitious goal of supplying electricity to Microsoft as early as 2028. This contract, however, will be fulfilled by a larger, commercial-scale reactor named Orion, which is currently under construction, rather than the Polaris prototype. This aggressive timeline highlights Helion’s confidence in its technological roadmap and its commitment to accelerating the deployment of fusion power.

It is important to note that each fusion company’s developmental path is intrinsically linked to the unique design of its reactor. For instance, Commonwealth Fusion Systems, employing a tokamak design—a doughnut-shaped device that uses powerful magnetic fields to contain the plasma—needs to heat its plasmas to over 100 million degrees Celsius. Helion’s reactor, in contrast, operates on a different principle and requires significantly higher temperatures, approximately twice as hot, to function optimally. This divergence in design philosophy and operational requirements dictates unique milestones and technological challenges for each entity.

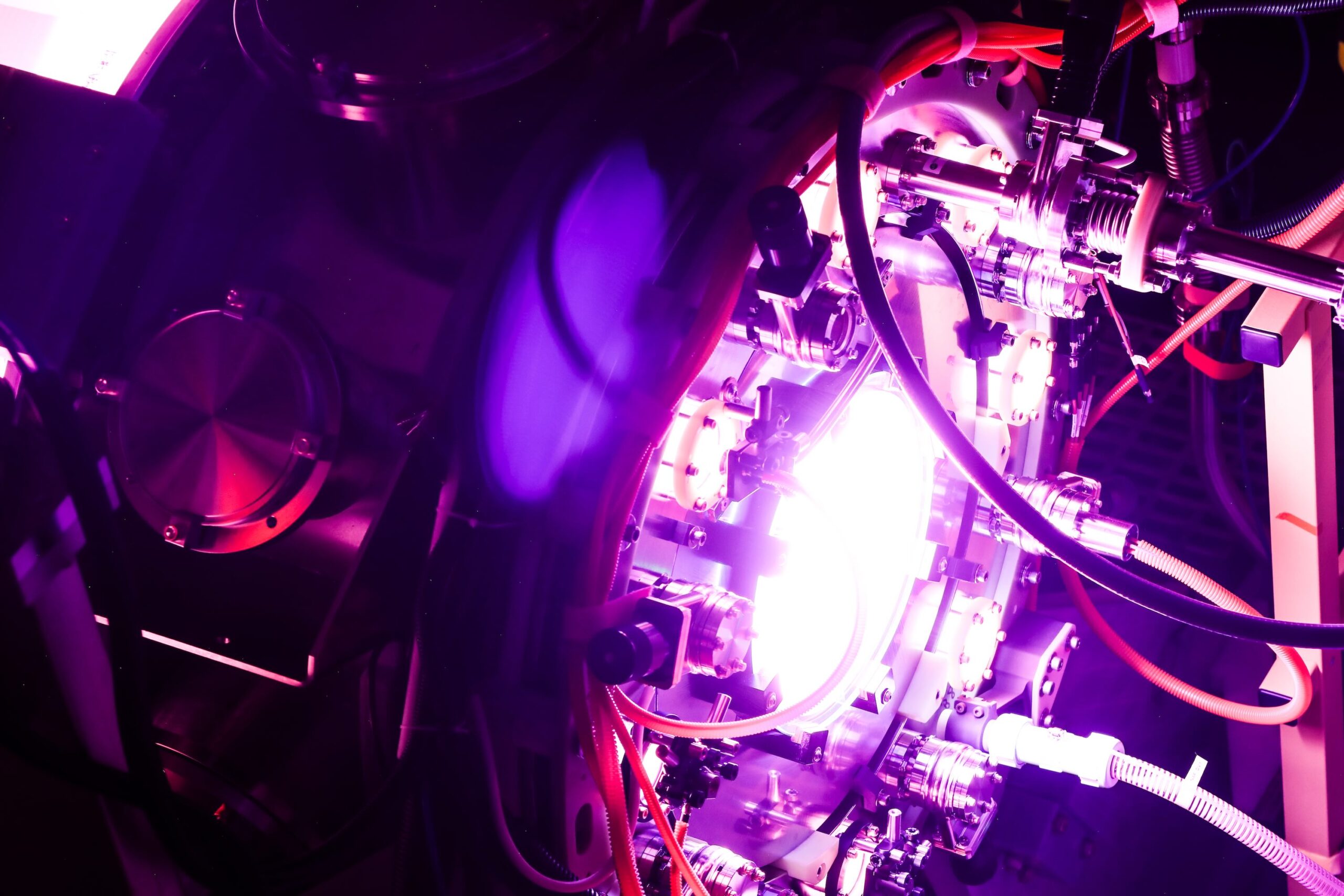

Helion’s innovative approach is rooted in its field-reversed configuration (FRC) reactor design. The internal chamber of the FRC resembles an hourglass. At its wider ends, fuel is injected and transformed into plasma. Powerful magnets then accelerate these plasmas towards the center, where they collide and merge. In the initial stages of this merger, the plasma reaches temperatures between 10 million and 20 million degrees Celsius. Subsequent compression by even more potent magnets drives the temperature up to the remarkable 150 million degrees Celsius achieved by Polaris, all within a fraction of a millisecond.

A key differentiator in Helion’s strategy is its method of energy extraction. Instead of relying on converting fusion energy into heat to drive turbines, as is common in many other fusion approaches, Helion harnesses the inherent magnetic field generated by the fusion reactions themselves. Each plasma pulse generates a powerful outward force that pushes against the reactor’s confining magnets, inducing an electrical current that can be directly harvested. This direct energy conversion method, the company believes, offers a significant advantage in terms of efficiency compared to its competitors.

Over the past year, Kirtley revealed that Helion has meticulously refined the electrical circuits within the reactor. These enhancements have been instrumental in boosting the amount of electricity that can be recovered from each fusion pulse, further optimizing the system’s performance.

While Helion is currently utilizing deuterium-tritium fuel for its experiments, its long-term vision involves transitioning to deuterium-helium-3 fuel. This fuel choice is strategic. Deuterium-helium-3 fusion produces a higher proportion of charged particles compared to deuterium-tritium fusion. These charged particles interact more forcefully with the magnetic fields confining the plasma, making them ideally suited for Helion’s direct electricity generation approach. Most other fusion companies are focused on deuterium-tritium and extracting energy as heat, a path that often involves more complex thermal management systems.

Helion’s ultimate objective is to achieve plasma temperatures of 200 million degrees Celsius, a target significantly higher than those pursued by many other fusion ventures. "We believe that at 200 million degrees, that’s where you get into that optimal sweet spot of where you want to operate a power plant," Kirtley stated, emphasizing the scientific rationale behind this ambitious temperature goal. This higher temperature is crucial for maximizing the efficiency and power output of their FRC design.

When questioned about whether Helion had reached scientific breakeven—the critical point where a fusion reaction generates more energy than is consumed to initiate and sustain it—Kirtley offered a nuanced response. "We focus on the electricity piece, making electricity, rather than the pure scientific milestones," he explained. This indicates a pragmatic approach, prioritizing the generation of usable power over purely academic benchmarks.

The challenge of sourcing helium-3, a relatively scarce element on Earth, is a key consideration for Helion’s future fuel cycle. While abundant on the Moon, its terrestrial availability necessitates an in-situ production strategy. Initially, Helion will fuse deuterium nuclei to generate its first batches of helium-3. In its regular operational mode, while deuterium-helium-3 fusion will be the primary power source, some deuterium-on-deuterium reactions will also occur. These reactions will produce additional helium-3, which the company will then purify and recirculate, creating a self-sustaining fuel loop.

The development of this sophisticated fuel cycle has been a subject of ongoing refinement. "It’s been a pleasant surprise in that a lot of that technology has been easier to do than maybe we expected," Kirtley commented, expressing optimism about the progress made. Helion has demonstrated the ability to produce helium-3 "at very high efficiencies in terms of both throughput and purity," a testament to their engineering prowess.

While Helion currently stands alone among fusion startups in its pursuit of helium-3 fuel, Kirtley anticipates this will change. He foresees other companies eventually adopting this fuel strategy as they recognize the benefits of direct electricity recovery. "Other folks—as they come along and recognize that they want to do this approach of direct electricity recovery and see the efficiency gains from it—will want to be using helium-3 fuel as well," he predicted, hinting at potential future collaborations or even fuel supply agreements.

Parallel to its experimental work with the Polaris prototype, Helion is actively engaged in the construction of Orion, a 50-megawatt fusion reactor designed to meet its contractual obligations with Microsoft. "Our ultimate goal is not to build and deliver Polaris," Kirtley clarified. "That’s a step along the way towards scaled power plants." Orion represents the next crucial phase in Helion’s journey, transitioning from experimental validation to a demonstrable power generation unit. This project is a critical testbed for the company’s technology at a scale that can begin to impact the energy market. The successful operation of Orion will be a strong indicator of Helion’s readiness to deploy commercial fusion power plants. The company’s methodical approach, progressing from smaller prototypes to larger, grid-connected systems, is a common and sensible strategy in the development of complex energy technologies. The journey from the laboratory to widespread commercial deployment is fraught with challenges, but Helion’s recent achievements and strategic partnerships suggest they are well-positioned to navigate this path.