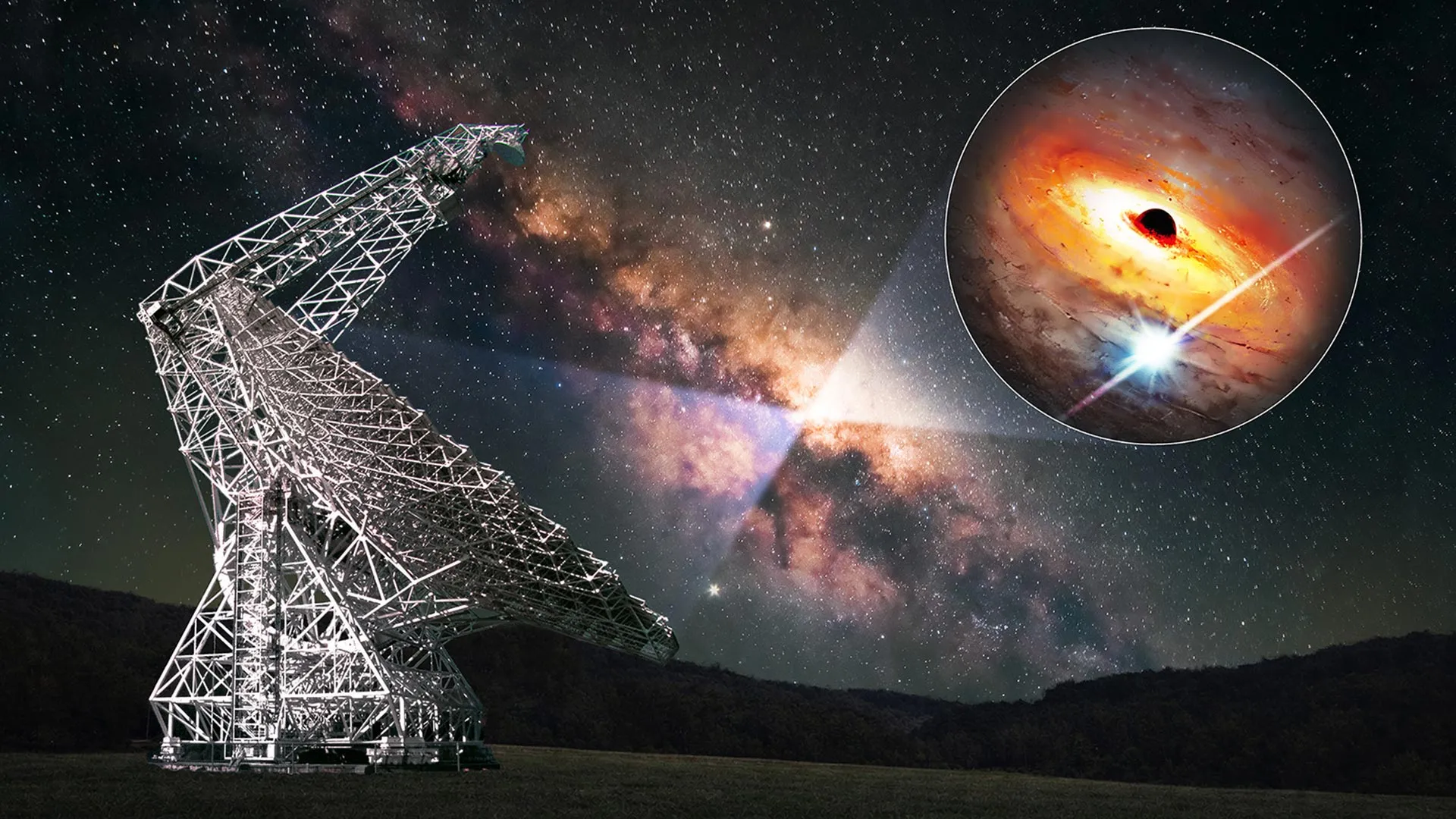

The Breakthrough Listen Galactic Center Survey embarked on an ambitious quest to peer into the heart of our home galaxy, a region teeming with stars, gas, dust, and the enigmatic supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A (Sgr A). During this intensive observational campaign, the research team identified a remarkably promising 8.19-millisecond pulsar (MSP) candidate situated in startling proximity to Sgr A*. The detection of such an object in this extreme gravitational crucible immediately signals its profound potential scientific significance.

A Potential Tool for Testing Einstein’s General Relativity in the Ultimate Laboratory

The identification of this millisecond pulsar candidate represents far more than just another celestial body. If astronomers can confirm the object’s existence and precisely measure the timing of its incredibly regular pulses, it would create an exceedingly rare and unparalleled opportunity to test Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity under the most extreme conditions imaginable. Tracking a pulsar in the immediate vicinity of a supermassive black hole would allow scientists to make exquisitely accurate measurements of space-time warping and gravitational effects in an environment where these phenomena are amplified to their absolute maximum. This would provide a natural laboratory for probing the limits of our understanding of gravity, potentially revealing new physics or confirming Einstein’s predictions with unprecedented precision.

Pulsars themselves are fascinating cosmic entities. They are the super-dense remnants of massive stars that have exhausted their nuclear fuel and collapsed under their own gravity, resulting in incredibly compact objects known as neutron stars. These neutron stars spin rapidly, often hundreds of times per second, and possess incredibly intense magnetic fields. As they spin, these magnetic fields generate focused beams of radio waves that sweep across the cosmos, much like the rotating beam of a lighthouse. When one of these beams happens to sweep across Earth, we detect a precise, periodic pulse of radio emission.

What makes pulsars, particularly millisecond pulsars (MSPs), so invaluable to astrophysics is the remarkable consistency of their signals. When undisturbed by outside forces, the radio pulses from a pulsar reach Earth with a stability that rivals atomic clocks. This extraordinary rhythmic precision allows pulsars to function as highly reliable cosmic clocks. Millisecond pulsars, spinning at rates of hundreds of rotations per second, are especially stable and predictable in their timing behavior, making them the most accurate celestial timekeepers known. Their consistent "ticking" can be perturbed by even the slightest external influence, making them incredibly sensitive probes of their environment.

How Gravity Can Distort a Pulsar’s Signal: A Relativistic Playground

The immense gravitational field of Sagittarius A* (estimated to contain about 4 million times the mass of our Sun) exerts a powerful and far-reaching gravitational influence that profoundly affects any nearby objects, including the fabric of space-time itself. It is precisely this extreme environment that makes the newly discovered pulsar candidate so exciting for fundamental physics.

Slavko Bogdanov, a research scientist at the Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory and a co-author on the study, elaborated on this critical aspect: "Any external influence on a pulsar, such as the gravitational pull of a massive object, would introduce anomalies in this steady arrival of pulses, which can be measured and modeled. In addition, when the pulses travel near a very massive object, they may be deflected and experience time delays due to the warping of space-time, as predicted by Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity."

The specific phenomena that could be observed if this pulsar candidate is confirmed and its orbit precisely mapped include:

- Orbital Decay due to Gravitational Wave Emission: While already observed in binary pulsars (e.g., PSR B1913+16, for which Hulse and Taylor won the Nobel Prize), a pulsar orbiting a supermassive black hole would experience vastly different gravitational wave emission characteristics, offering a new test regime.

- Relativistic Precession of the Orbit: The pulsar’s orbit itself would not be a perfect ellipse but would precess (rotate) over time, a phenomenon analogous to the anomalous precession of Mercury’s orbit, but dramatically enhanced by the proximity to Sgr A*.

- Shapiro Delay: As the pulsar’s pulses travel through the warped space-time near Sgr A* on their way to Earth, they would experience a measurable delay. This "Shapiro delay" is a direct consequence of space-time curvature and provides one of the most robust tests of General Relativity.

- Gravitational Lensing and Deflection: The radio beams themselves would be deflected by the strong gravity of Sgr A*, potentially altering the observed pulse shape or arrival times depending on the alignment.

These effects, while subtle in weaker gravitational fields, would be magnified near Sgr A to a degree that could provide unprecedented constraints on alternative theories of gravity that diverge from Einstein’s predictions in strong-field regimes. For instance, observations of stellar orbits around Sgr A have already provided compelling evidence for the existence of the black hole and insights into its mass, but a pulsar would offer a probe of far greater precision, directly mapping the space-time curvature rather than just the orbital dynamics of massive objects.

The Challenges of Observing the Galactic Center

The Galactic Center is not just gravitationally extreme; it is also an incredibly challenging region for astronomical observation, particularly in radio wavelengths. The path between Earth and Sgr A* is dense with ionized gas, dust, and strong magnetic fields. These factors contribute to several phenomena that can obscure or distort radio signals:

- Dispersion: Free electrons in the interstellar medium cause radio waves of different frequencies to travel at different speeds, "dispersing" the pulse. This effect must be carefully corrected for, and the large amount of dispersion near the Galactic Center means conventional search techniques are often less effective.

- Scattering: Turbulence in the ionized gas can scatter radio waves, smearing out the sharp pulses of a pulsar and making them appear broadened or even undetectable. This "multi-path scattering" is particularly severe in the inner few parsecs of the galaxy.

- Absorption and Obscuration: Dust and gas clouds can absorb or block radio signals at certain wavelengths.

- High Background Noise: The Galactic Center is a cacophony of radio emission from supernova remnants, star-forming regions, and other sources, creating a high background noise level that can drown out faint pulsar signals.

The Breakthrough Listen Galactic Center Survey was specifically designed to overcome many of these challenges. Its instruments and analysis techniques were optimized for high sensitivity and broad frequency coverage, allowing researchers to detect faint, highly dispersed, and scattered signals that might otherwise be missed. The sheer "sensitivity" mentioned in the article’s opening is paramount to this success, enabling the detection of signals that have traversed the turbulent interstellar medium.

Follow-Up Observations Underway: From Candidate to Confirmation

Given the immense scientific significance of this potential discovery, the research team is not resting on its laurels. Rigorous follow-up observations are now underway to determine whether the pulsar candidate is indeed genuine. The process of confirming a pulsar involves several steps:

- Re-detection: Repeated observations at different times are crucial to confirm the periodic nature of the signal and rule out transient interference or spurious detections.

- Timing Analysis: Precise measurements of the pulse arrival times over extended periods are needed to establish the pulsar’s spin period, its rate of slowing down (spin-down rate), and crucially, any variations caused by orbital motion around another object.

- Multi-Wavelength Observations: While radio observations are primary, complementary observations at other wavelengths (e.g., X-ray, gamma-ray if the pulsar is energetic enough) can provide additional clues about its nature and environment.

- Orbital Solution: If the pulsar is indeed in orbit around Sgr A*, its orbital parameters (period, eccentricity, inclination) would need to be precisely determined through long-term timing observations. This is the most challenging but also the most rewarding aspect for testing General Relativity.

Karen I. Perez, the lead author, expressed the team’s anticipation: "We’re looking forward to what follow-up observations might reveal about this pulsar candidate. If confirmed, it could help us better understand both our own Galaxy, and General Relativity as a whole." The journey from a promising candidate to a confirmed, well-characterized pulsar is often long and arduous, requiring dedicated telescope time and sophisticated data analysis. However, the potential rewards in this case are so extraordinary that the effort is more than justified.

Open Science and Broader Collaboration

In line with the principles of open science and to encourage broader scientific collaboration, Breakthrough Listen is making the data from this survey publicly available. This open-data policy allows research teams around the world to conduct their own independent analyses, verify the findings, and explore related scientific questions that might extend beyond the initial scope of the Columbia University team. This collaborative approach accelerates scientific progress, fosters new discoveries, and ensures the robustness of findings through independent scrutiny. It also allows other researchers with different expertise or computational resources to contribute to the challenging task of sifting through vast amounts of radio astronomy data.

The Breakthrough Listen initiative, while primarily known for its ambitious search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI), also funds and conducts cutting-edge astrophysical research that leverages its powerful observational capabilities. The search for pulsars, especially in extreme environments, perfectly aligns with this dual mission, as the same sensitive instruments and data analysis pipelines used for SETI can also be employed to uncover novel astrophysical phenomena. The detection of a pulsar near Sgr A* demonstrates the profound scientific dividends yielded by such high-sensitivity surveys, regardless of whether they ultimately find signs of intelligent life.

The Broader Context: Pulsars and the Galactic Center

The search for pulsars in the Galactic Center is not just about testing General Relativity. It’s also critical for understanding the extreme environment around a supermassive black hole. The presence or absence of pulsars, their distribution, and their properties can tell us about:

- Star Formation and Evolution: Pulsars are the end products of massive stars. Their distribution can provide clues about recent star formation activity in the Galactic Center.

- Stellar Dynamics: The orbits of pulsars can trace the gravitational potential of the central region, including the influence of dark matter or other unseen mass.

- Interstellar Medium: The dispersion and scattering properties of pulsar signals provide unique diagnostics of the ionized gas and magnetic fields in the Galactic Center, helping us to map this complex medium.

- Gravitational Wave Detectors: A network of precisely timed pulsars distributed across the galaxy could form a "pulsar timing array," a natural gravitational wave observatory capable of detecting ultra-low-frequency gravitational waves, such as those emitted by merging supermassive black holes in distant galaxies. While this pulsar candidate is too close to Sgr A* to be part of such an array due to its own relativistic perturbations, its existence contributes to the overall understanding of pulsar populations.

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) has recently provided the first-ever image of Sgr A*, revealing its shadow and confirming its black hole nature. While the EHT operates at millimeter wavelengths and probes the immediate vicinity of the event horizon, a pulsar provides a different, complementary probe. Its precise timing acts as a distant but highly sensitive clock, measuring the space-time distortions caused by the black hole from its orbital perch. The combination of these observational techniques offers a multi-faceted approach to unraveling the mysteries of our galaxy’s heart.

In conclusion, the discovery of an 8.19-millisecond pulsar candidate near Sagittarius A* by the Breakthrough Listen Galactic Center Survey, led by Karen I. Perez at Columbia University, represents a monumental stride in astrophysics. If confirmed, this celestial clock will not only serve as an unprecedented laboratory for testing Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity in the most extreme gravitational environment known but will also deepen our understanding of the dynamics and evolution of the Milky Way’s turbulent core. The ongoing follow-up observations and the commitment to open science underscore the collaborative and rigorous nature of modern astronomical research, promising exciting new insights into the fundamental laws governing our universe.