New research from The University of Texas at Austin, published in the prestigious journal Nature, now presents compelling evidence that may finally resolve this long-standing puzzle. The team focused their investigation on a fascinating group of microbes known as Asgard archaea, which are widely recognized by the scientific community as the closest living relatives to the ancestors of all eukaryotic life. While the prevailing understanding has been that most known Asgard archaea inhabit deep-sea hydrothermal vents, anoxic sediments, or other oxygen-deprived environments, the groundbreaking new study demonstrates that some members of this crucial lineage possess the remarkable ability to tolerate or even actively utilize oxygen. This pivotal discovery not only strengthens the long-standing theory that complex life evolved as predicted but crucially refines our understanding of the specific environmental conditions—likely involving the presence of oxygen—under which this transformative event occurred.

"Most Asgards alive today have been found in environments without oxygen," explained Brett Baker, an associate professor of marine science and integrative biology at UT Austin and a leading expert in microbial evolution. "But it turns out that the ones most closely related to eukaryotes live in places with oxygen, such as shallow coastal sediments and floating in the water column, and they have a lot of metabolic pathways that use oxygen. That suggests that our eukaryotic ancestor likely had these processes, too." This statement directly challenges the previously accepted anaerobic nature of the eukaryotic host, suggesting a more nuanced and adaptable ancestor than previously imagined. The implications are profound, shifting the paradigm of early eukaryote evolution and aligning it more seamlessly with the planet’s geochemical history.

The Great Oxidation Event and the Emergence of Early Eukaryotes

The findings from Baker’s team, meticulously detailed through extensive genomic analysis, align strikingly well with reconstructions of Earth’s early atmosphere as pieced together by geologists and paleontologists. For billions of years, Earth’s atmosphere was largely devoid of free oxygen, dominated instead by gases like nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane. Then, approximately 2.4 to 2.1 billion years ago, a monumental shift occurred: oxygen concentrations in the atmosphere began to rise sharply during what scientists term the Great Oxidation Event (GOE). This dramatic period, primarily driven by the proliferation of oxygen-producing cyanobacteria, transformed Earth’s surface and oceans, eventually approaching oxygen levels similar to those found today. This rise wasn’t a smooth, continuous increase but likely involved several fluctuating "whiffs" of oxygen before a more sustained accumulation.

What makes the timing particularly compelling for the origin of eukaryotes is that within a few hundred million years—a blink of an eye in geological terms—of this dramatic increase in atmospheric oxygen, the earliest known microfossils of eukaryotes appear in the fossil record. This remarkably close temporal correlation has long suggested that oxygen, far from being a mere backdrop, may have played a crucial, perhaps even indispensable, role in the emergence and diversification of complex life. The new research provides the biochemical bridge to connect these two major evolutionary and geological events.

"The fact that some of the Asgards, which are our ancestors, were able to use oxygen fits in with this very well," Baker affirmed. "Oxygen appeared in the environment, and Asgards adapted to that. They found an energetic advantage to using oxygen, and then they evolved into eukaryotes." This narrative paints a picture of evolutionary opportunism, where the Asgard host cell, rather than being confined to anoxic refugia, actively embraced the newly available oxygen, leveraging its chemical reactivity for more efficient energy production. This adaptation would have been a powerful selective pressure, favoring those archaeal lineages capable of metabolizing oxygen and potentially setting the stage for the next great leap in complexity.

Symbiosis and the Birth of Mitochondria: A Refined Hypothesis

The prevailing model for the origin of eukaryotes, known as the endosymbiotic theory, posits that eukaryotes arose when an ancestral Asgard archaeon formed a profound symbiotic relationship with an alphaproteobacterium. This partnership was not merely cohabitation; over evolutionary time, the two organisms became so intimately integrated that they essentially merged into a single, novel cellular entity. The alphaproteobacterium, once a free-living bacterium, eventually lost much of its independent genetic material and evolved into the mitochondria—the powerhouse organelles found within nearly all eukaryotic cells, responsible for producing the vast majority of cellular energy (ATP) through oxidative phosphorylation.

The "hydrogen hypothesis," a prominent model for the initial stages of this symbiosis, suggested that the archaeal host was an anaerobic methanogen that benefited from hydrogen produced by the symbiotic bacterium, which was itself anaerobic. However, this model struggled with the subsequent evolution of aerobic mitochondria. The new findings offer a more elegant solution: if the Asgard host was already capable of oxygen metabolism, the transition to housing an aerobic bacterium (which would become the mitochondrion) becomes far less problematic and more energetically favorable from the outset. The archaeal host would have already possessed mechanisms to deal with and even exploit oxygen, making the integration of an oxygen-respiring partner a logical next step rather than a physiological leap into the unknown. This pre-adaptation to oxygen would have provided a crucial selective advantage, allowing the nascent eukaryote to harness the immense energetic potential of oxygen-based respiration.

In this landmark study, researchers significantly expanded the known genetic diversity of Asgard archaea. Their efforts led to the identification of specific groups, notably the Heimdallarchaeia, which exhibit an especially close phylogenetic relationship to eukaryotes but are relatively uncommon and thus often overlooked in standard environmental sequencing efforts today. The name "Heimdallarchaeia" itself is fitting, referencing Heimdall, the Norse god who guards the Bifröst bridge between worlds—a metaphor for their bridging position between prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

"These Asgard archaea are often missed by low-coverage sequencing," said co-author Kathryn Appler, a postdoctoral researcher at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, France, who spearheaded much of the initial genomic work. "The massive sequencing effort and layering of sequence and structural methods enabled us to see patterns that were not visible prior to this genomic expansion." This underscores the technical challenges inherent in studying these elusive organisms and highlights the scale of the team’s achievement in uncovering their hidden diversity.

A Massive Genome Sequencing Effort: Unveiling Hidden Life

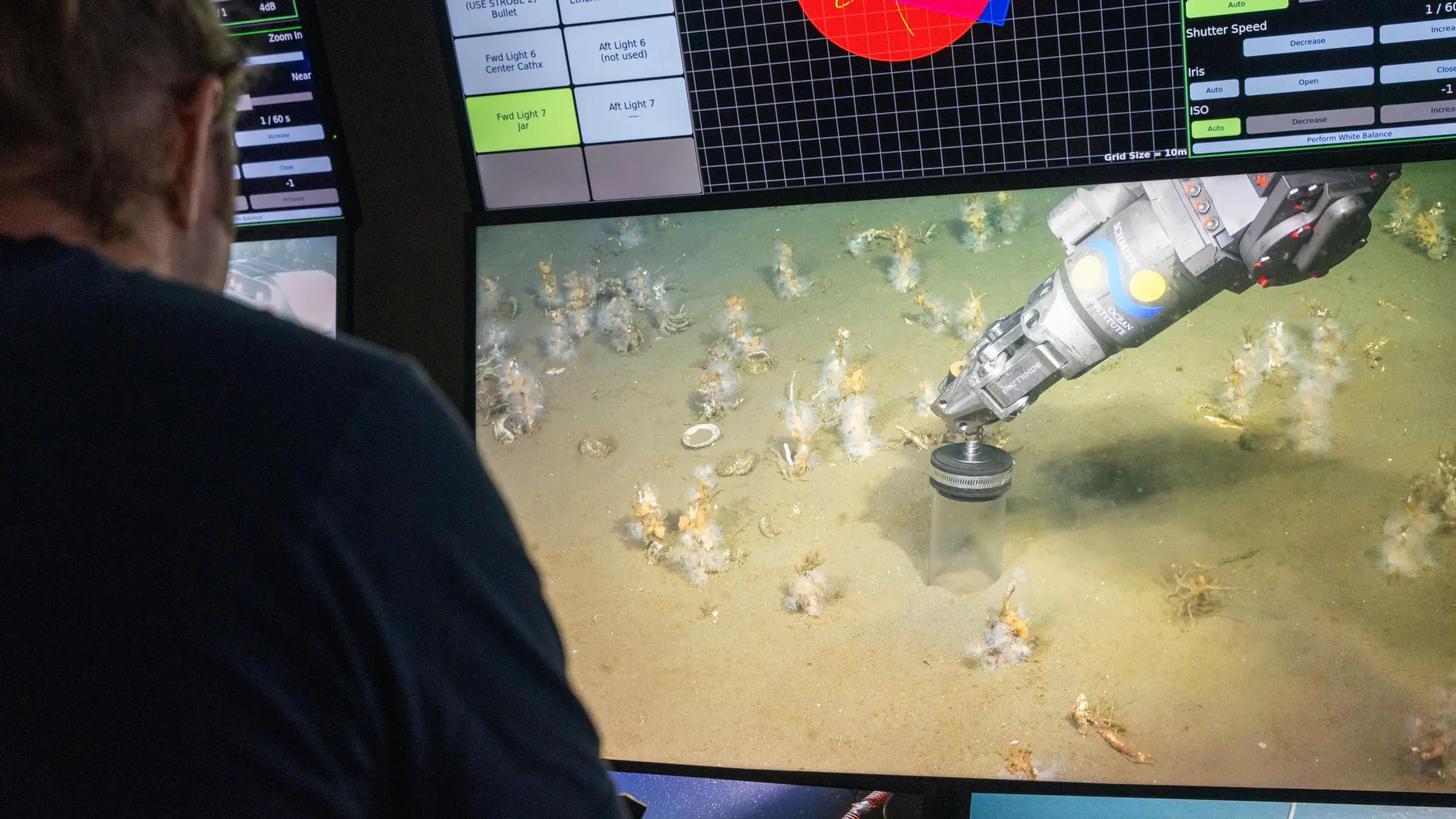

The monumental work began with Appler’s Ph.D. research at The University of Texas Marine Science Institute in 2019, where she meticulously extracted DNA from marine sediments. What started as a focused project soon blossomed into a colossal undertaking. The UT team, in collaboration with a global network of researchers, ultimately assembled an astonishing collection of more than 13,000 new microbial genomes. This ambitious project combined samples from multiple marine expeditions spanning diverse environments, from shallow coastal waters to deep-sea trenches, and necessitated the analysis of roughly 15 terabytes of environmental DNA—a data volume that speaks to the sheer scale of modern metagenomic research.

From this extensive and unprecedented dataset, the researchers successfully recovered hundreds of new Asgard archaeal genomes. This achievement nearly doubled the known genomic diversity of the entire group, offering an unparalleled glimpse into the evolutionary history and metabolic capabilities of these critical microbes. By meticulously comparing genetic similarities and differences across this expanded dataset, the team was able to construct a significantly more comprehensive and refined Asgard archaea "tree of life." This updated phylogeny not only clarified the evolutionary relationships within the Asgard superphylum but also solidified the position of Heimdallarchaeia as the most direct relatives of eukaryotes. The newly identified genomes also revealed previously unknown protein groups, doubling the number of recognized enzymatic classes within these microbes, hinting at a much richer and more diverse metabolic repertoire than previously appreciated.

AI Analysis of Oxygen Metabolism Proteins: A Structural Revelation

One of the most innovative aspects of the study involved leveraging cutting-edge artificial intelligence to delve deeper into the functional implications of their genomic discoveries. The team specifically focused on the Heimdallarchaeia, comparing their predicted proteins to those found in eukaryotes that are known to be involved in energy production and, crucially, oxygen metabolism. To accomplish this, they utilized a revolutionary artificial intelligence system called AlphaFold2. Developed by Google’s DeepMind, AlphaFold2 has transformed structural biology by accurately predicting the three-dimensional shapes of proteins from their amino acid sequences. This capability is paramount because a protein’s intricate structure dictates its precise function. Thus, understanding the structure provides invaluable insights into how a protein interacts with other molecules and performs its biological role.

The results of this sophisticated AI-powered analysis were striking and highly informative. The AlphaFold2 predictions showed that several Heimdallarchaeia proteins closely resemble those utilized by eukaryotic cells for oxygen-based, highly energy-efficient metabolism, particularly components of the electron transport chain involved in respiration. This remarkable structural similarity offers powerful additional support for the groundbreaking idea that the ancestors of complex life were not only tolerant of oxygen but were already adapted to actively using it for energy generation. This structural evidence provides a robust molecular-level validation for the genomic and phylogenetic data, cementing the team’s conclusion that the oxygen paradox has finally been resolved.

The collaborative nature of this extensive research effort is also noteworthy, bringing together expertise from various institutions. Other key contributors to the study included former UT researchers Xianzhe Gong (currently at Shandong University in China), Pedro Leão (now at Radboud University in the Netherlands), Marguerite Langwig (now at the University of Wisconsin-Madison) and Valerie De Anda (currently at the University of Vienna). Further significant contributions came from James Lingford and Chris Greening at Monash University in Australia, along with Kassiani Panagiotou and Thijs Ettema at Wageningen University in the Netherlands—the latter being a group renowned for their pioneering work on Asgard archaea.

This monumental research was made possible through substantial funding from prestigious scientific organizations, including the Gordon and Betty Moore and Simons Foundations, which are dedicated to advancing fundamental scientific discovery. Additional support was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, highlighting the international scope and importance of this investigation into the very origins of complex life on Earth. The implications of this study are far-reaching, not only settling a long-standing debate in evolutionary biology but also opening new avenues for understanding microbial adaptation, the interplay between geochemistry and life, and ultimately, our own evolutionary journey.