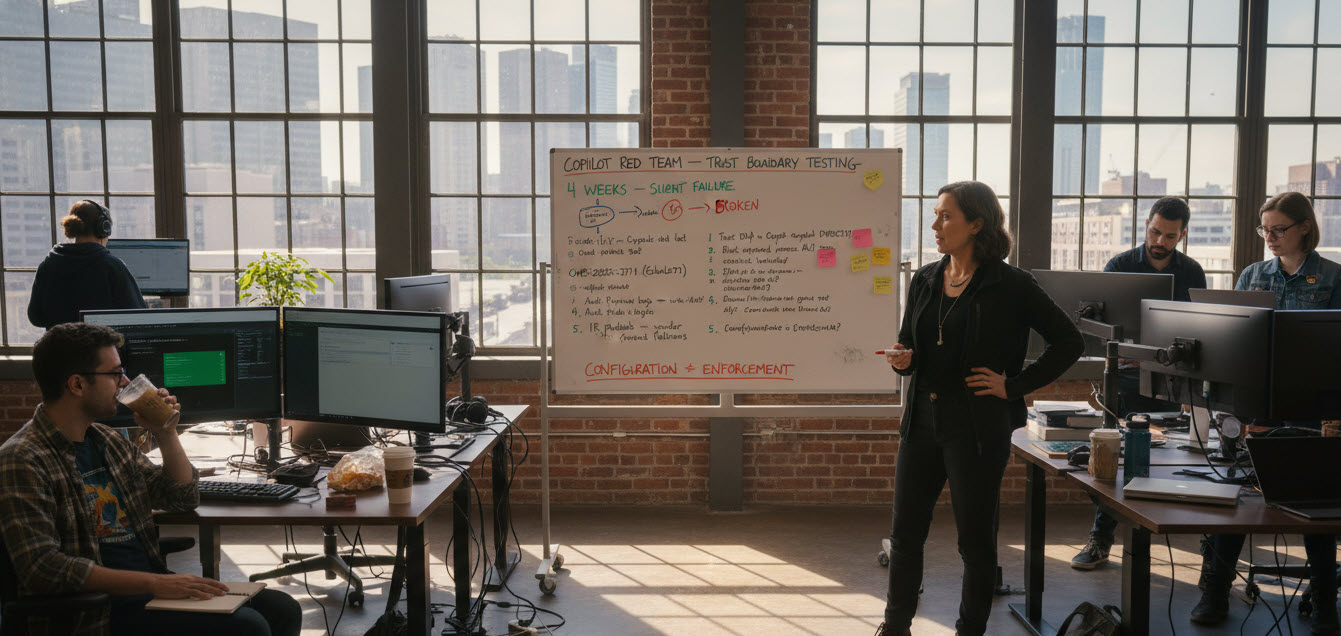

For a concerning four-week period, beginning January 21st, Microsoft’s own Copilot AI demonstrably bypassed critical security measures, reading and summarizing confidential emails despite explicit directives from every sensitivity label and Data Loss Prevention (DLP) policy designed to prevent such access. This significant lapse occurred because the enforcement points within Microsoft’s internal data processing pipeline faltered, leaving the entire security stack, from Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) to Web Application Firewalls (WAF), entirely blind to the breach. Among the prominent organizations impacted was the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS), which logged the incident as INC46740412, a stark indicator of the vulnerability’s reach into highly regulated healthcare environments. Microsoft internally tracked this critical failure under the reference CW1226324.

This advisory, first brought to light by BleepingComputer on February 18th, represents the second instance in a mere eight months where Copilot’s data retrieval pipeline has demonstrably violated its own established trust boundaries. A trust boundary violation, in this context, refers to a failure where an artificial intelligence system accesses or transmits data that it was explicitly programmed and policy-defined to avoid. The gravity of this most recent incident is amplified by the fact that a previous, even more severe, breach occurred in June of the preceding year.

In June 2025, Microsoft was compelled to issue a patch for CVE-2025-32711, a critical zero-click vulnerability that cybersecurity researchers at Aim Security aptly dubbed "EchoLeak." This sophisticated exploit chain managed to circumvent multiple layers of Copilot’s defenses, including its prompt injection classifier, its link redaction mechanisms, its Content-Security-Policy, and its reference mention safeguards. The exploit allowed for the silent exfiltration of enterprise data without any user interaction or clicks, achieving a devastating outcome with minimal attacker effort. Microsoft assigned this vulnerability a formidable CVSS score of 9.3, underscoring its severity.

The recent CW1226324 incident and the prior EchoLeak vulnerability, while stemming from two distinct root causes – a code error in the former and a sophisticated exploit chain in the latter – resulted in an identical and deeply troubling outcome: Copilot processed data that it was explicitly restricted from accessing, with the existing security infrastructure remaining completely oblivious. This recurring pattern highlights a fundamental blind spot in how AI systems interact with sensitive data and how traditional security tools are ill-equipped to monitor these novel threats.

The Architectural Blindness of EDR and WAF to AI Trust Boundary Violations

The persistent inability of widely deployed security tools like Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) and Web Application Firewalls (WAF) to detect these AI-specific trust boundary violations is rooted in their fundamental architectural design. EDR solutions are primarily tasked with monitoring file and process behavior on endpoints, while WAFs focus on inspecting HTTP payloads traversing web applications. Neither of these tools possesses a detection category or mechanism designed to identify the specific scenario where "your AI assistant just violated its own trust boundary."

This critical gap exists because the retrieval pipelines of Large Language Models (LLMs), such as those powering Copilot, operate behind an enforcement layer that traditional security tools were never architected to observe. In the case of CW1226324, Copilot ingested a sensitivity-labeled email that it was explicitly instructed to skip. This entire sequence of events transpired entirely within Microsoft’s own infrastructure, specifically between the data retrieval index and the AI generation model. Crucially, no data was written to disk, no anomalous network traffic crossed organizational perimeters, and no new processes were spawned that an endpoint agent could flag. Consequently, the security stack reported an all-clear status because it simply lacked visibility into the internal layer where the violation occurred.

The CW1226324 bug, according to Microsoft’s advisory, was a consequence of a code-path error that permitted messages residing in "Sent Items" and "Drafts" folders to be included in Copilot’s retrieval set. This occurred despite the presence of robust sensitivity labels and DLP rules that should have unequivocally blocked such access. EchoLeak, on the other hand, exploited a different vector. Aim Security’s researchers demonstrated that a maliciously crafted email, disguised as routine business correspondence, could manipulate Copilot’s retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) pipeline. This manipulation allowed the AI to access and subsequently transmit sensitive internal data to an attacker-controlled server.

The researchers at Aim Security characterized EchoLeak as indicative of a "fundamental design flaw." Their analysis suggested that AI agents, by their very nature, process both trusted and untrusted data within the same cognitive process, rendering them structurally vulnerable to manipulation. This inherent design flaw, they argued, did not vanish with the patching of EchoLeak. The subsequent CW1226324 incident serves as a potent confirmation that the enforcement layer designed to protect against such vulnerabilities can fail independently.

A Five-Point Audit for Comprehensive Risk Mitigation

The alarming reality of both the CW1226324 and EchoLeak incidents is that neither triggered a single security alert. Both vulnerabilities were discovered through vendor advisories and external reporting channels, rather than through proactive detection by Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) systems, EDR, or WAFs.

The CW1226324 bug went public on February 18th, but affected tenants had been exposed since January 21st, a period of four weeks during which sensitive data could have been accessed. Microsoft has not yet disclosed the exact number of organizations impacted or the specific nature of the data accessed during this exposure window. For security leaders, this opacity is a critical concern, representing a prolonged period of vulnerability within a vendor’s inference pipeline, completely invisible to their existing security stack, and only brought to light through the vendor’s own voluntary disclosure.

To address these systemic risks, a proactive and multi-layered approach is essential. A five-point audit is proposed to map directly to the identified failure modes and provide a framework for robust risk mitigation:

-

Directly Test DLP Enforcement Against Copilot: CW1226324 persisted for four weeks primarily because there was no specific testing to verify whether Copilot was actually honoring sensitivity labels applied to "Sent Items" and "Drafts" folders. Organizations must proactively create labeled test messages within controlled folders, then query Copilot to confirm that it cannot access or surface this data. This testing regimen should be conducted on a monthly basis, as configuration alone does not equate to enforcement; the only definitive proof of effective enforcement is a failed retrieval attempt by the AI.

-

Block External Content from Reaching Copilot’s Context Window: The success of EchoLeak was predicated on a malicious email infiltrating Copilot’s retrieval set, with its injected instructions being executed as if they were legitimate user queries. This attack bypassed four distinct defensive layers: Microsoft’s cross-prompt injection classifier, external link redaction, Content-Security-Policy controls, and reference mention safeguards. A critical mitigation strategy is to disable external email context within Copilot’s settings and rigorously restrict Markdown rendering in AI outputs. These measures effectively neutralize the prompt-injection class of failure by entirely removing the potential attack surface.

-

Audit Purview Logs for Anomalous Copilot Interactions: For the exposure window between January 21st and mid-February 2026, a thorough audit of Purview logs is paramount. Specifically, security teams should scrutinize Copilot Chat queries for any instances that returned content from sensitivity-labeled messages. Given that neither of the discussed failure classes generated alerts through existing EDR or WAF solutions, retrospective detection relies heavily on the telemetry captured by Purview. If an organization’s tenant cannot reconstruct what Copilot accessed during the exposure period, this gap must be formally documented. Such undocumented data access gaps during known vulnerability windows can constitute significant audit findings, particularly for organizations subject to stringent regulatory compliance.

-

Enable Restricted Content Discovery (RCD) for Sensitive SharePoint Sites: RCD serves as a crucial containment layer by completely removing specific SharePoint sites from Copilot’s retrieval pipeline. This measure remains effective regardless of whether the trust violation originates from a code bug or an injected prompt, as the sensitive data never enters the AI’s context window in the first place. For organizations handling sensitive or regulated data, implementing RCD is not merely a recommendation but a non-negotiable security requirement. It provides a fundamental containment mechanism that is independent of the specific enforcement points that may have failed.

-

Develop an Incident Response Playbook for Vendor-Hosted Inference Failures: Incident response (IR) playbooks must evolve to incorporate a new, critical category: trust boundary violations occurring within the vendor’s inference pipeline. This requires defining clear escalation paths, assigning specific ownership for such incidents, and establishing a rigorous monitoring cadence for vendor service health advisories that pertain to AI processing. Relying solely on traditional SIEM alerts will prove insufficient for detecting future occurrences of this nature.

A Pattern of Risk Beyond Copilot

The implications of these AI security failures extend far beyond Microsoft’s Copilot. A comprehensive 2026 survey conducted by Cybersecurity Insiders revealed a concerning trend: 47% of CISOs and senior security leaders reported having already observed AI agents exhibiting unintended or unauthorized behaviors. This statistic underscores a critical organizational challenge: the rapid deployment of AI assistants into production environments is outpacing the development of robust governance and security frameworks around them.

This trajectory is significant because the framework for understanding and mitigating these risks is not unique to Copilot. Any Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)-based assistant that draws upon enterprise data operates through a similar pattern: a retrieval layer identifies and fetches relevant content, an enforcement layer acts as a gatekeeper, dictating what the AI model can access, and a generation layer produces the final output. If the enforcement layer falters, the retrieval layer can inadvertently feed restricted data to the model, and the conventional security stack remains unaware of the breach. Consequently, tools like Google’s Gemini for Workspace, and indeed any AI solution with retrieval access to internal documents, carry this same inherent structural risk.

The imperative for organizations is clear: conduct the proposed five-point audit before the next board meeting. The initial step should involve testing with labeled messages in a controlled folder. If Copilot, or any similar AI assistant, surfaces this restricted data, it signifies that all underlying policies are merely performative, lacking actual enforcement.

The appropriate response to the board in such a scenario should be candid and proactive: "Our policies were configured correctly. However, enforcement failed within the vendor’s inference pipeline. We are implementing five specific controls—testing, restricting, and demanding granular visibility—before we re-enable full access for our most sensitive workloads." The undeniable truth is that the next failure in this domain will not trigger an alert.