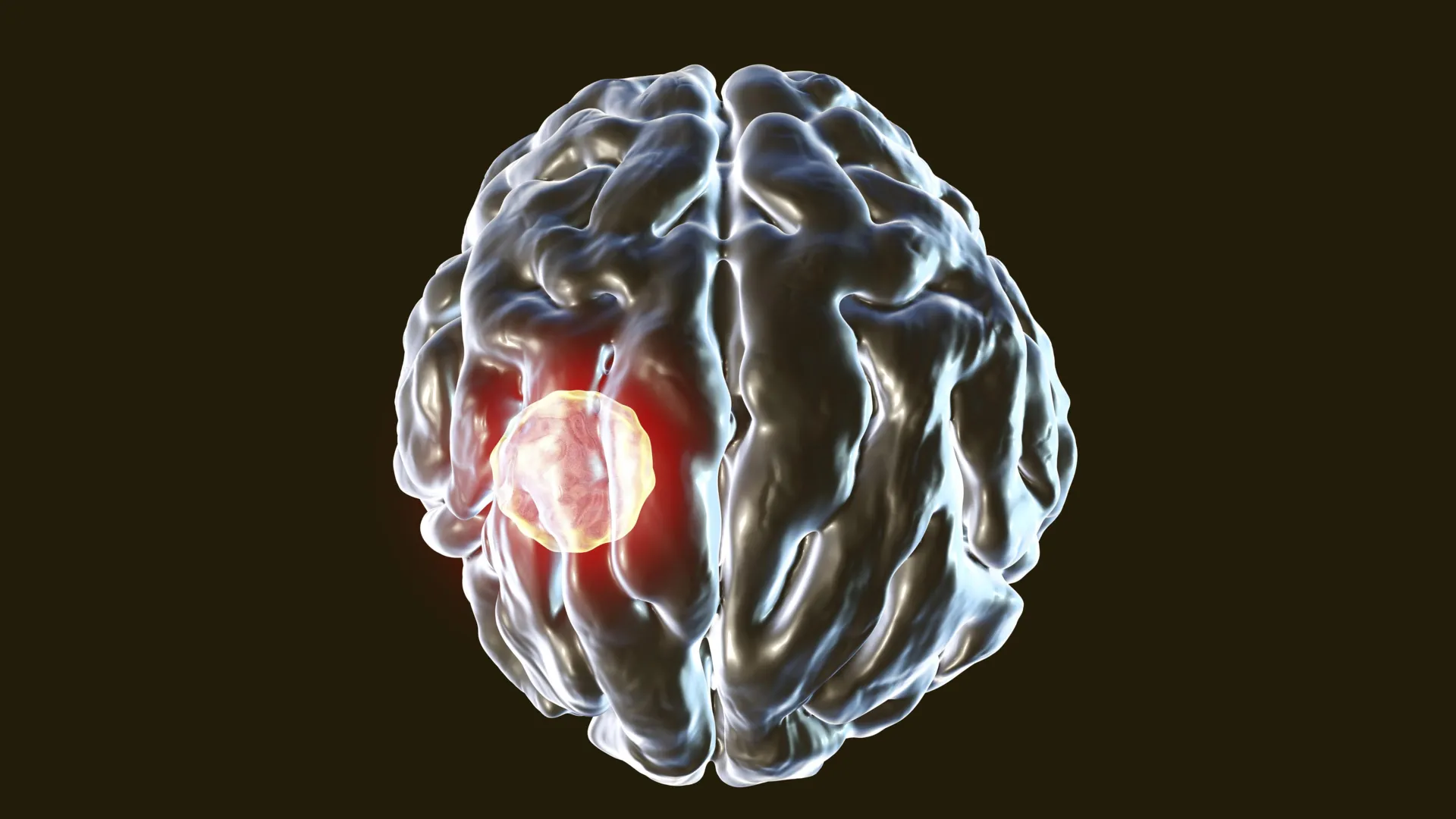

The silent invader, Toxoplasma gondii, a microscopic parasite with a global reach, represents one of humanity’s most widespread yet least understood persistent infections. Believed to reside within the brains of an astonishing one-third of the world’s population, this insidious organism poses a fascinating biological paradox: how do so many people host a potentially dangerous brain parasite without ever developing symptoms? New groundbreaking research emerging from UVA Health’s Center for Brain Immunology and Glia (BIG Center) sheds critical light on this mystery, revealing a sophisticated cellular "self-destruct" mechanism that allows the body to control Toxoplasma even when it infiltrates its most elite immune defenders.

Toxoplasma gondii is a master of stealth, a single-celled obligate intracellular parasite that primarily infects warm-blooded animals, including humans. Its life cycle is complex and involves felines, particularly domestic cats, as definitive hosts, where sexual reproduction occurs. Humans, along with other mammals and birds, serve as intermediate hosts. Infection pathways for humans are diverse and common: consumption of undercooked meat containing tissue cysts, accidental ingestion of oocysts from contaminated soil, water, or unwashed fruits and vegetables (often shed in cat feces), or, less commonly, through congenital transmission from mother to child during pregnancy, and organ transplantation or blood transfusions. Once ingested, the parasite swiftly disseminates throughout the body, eventually crossing the blood-brain barrier to establish lifelong residence in the brain and muscle tissues, forming microscopic cysts.

Despite its pervasive presence, the vast majority of infected individuals remain asymptomatic. For these healthy carriers, the immune system effectively walls off the parasites within dormant cysts, preventing active disease. However, the equilibrium can be precarious. When the immune system is compromised—such as in individuals undergoing chemotherapy, organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressants, or those living with HIV/AIDS—the dormant cysts can reactivate, leading to toxoplasmosis. This active disease can manifest in severe and life-threatening ways, including encephalitis, retinochoroiditis (eye inflammation), pneumonia, or disseminated infection affecting multiple organs. For pregnant women, a primary infection can lead to congenital toxoplasmosis in the fetus, potentially causing devastating neurological damage, blindness, or even miscarriage. Understanding how the immune system normally maintains control is therefore paramount, not only for basic biological insight but also for developing therapeutic strategies for vulnerable populations.

The focus of the UVA Health research, led by Dr. Tajie Harris, the director of the BIG Center at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, centered on a particularly perplexing aspect of this host-parasite interaction: the ability of Toxoplasma to infect CD8+ T cells. CD8+ T cells are often referred to as the "cytotoxic T lymphocytes" or "killer T cells." They are the immune system’s frontline assassins, specialized to identify and eliminate cells that have been infected by intracellular pathogens like viruses and certain bacteria, or that have become cancerous. Their role is to scan the body, recognize pathogen-derived antigens presented on the surface of infected cells, and then trigger the death of those cells, thereby preventing pathogen replication and spread. For Toxoplasma to successfully infect these very cells—the ultimate guardians against intracellular threats—presents a formidable challenge to the conventional understanding of immune defense.

"We know that T cells are really important for combatting Toxoplasma gondii, and we thought we knew all the reasons why. T cells can destroy infected cells or cue other cells to destroy the parasite. We found that these very T cells can get infected, and, if they do, they can opt to die. Toxoplasma parasites need to live inside cells, so the host cell dying is game over for the parasite," Dr. Harris explained, underscoring the revolutionary nature of their discovery. This finding flips the script on the typical T cell response. Instead of the T cell killing an already infected cell, the T cell itself becomes infected and then executes a self-sacrifice, taking the parasite with it. "Understanding how the immune system fights Toxoplasma is important for several reasons. People with compromised immune systems are vulnerable to this infection, and now we have a better understanding of why and how we can help patients fight this infection."

Caspase-8 and the Self-Destruct Defense: A Critical Breakthrough

The molecular lynchpin of this remarkable self-destruct defense mechanism, as discovered by Harris and her team, is a powerful enzyme called caspase-8. Caspases are a family of cysteine-dependent aspartate-specific proteases that play central roles in programmed cell death (apoptosis) and inflammation. Caspase-8, in particular, is a crucial initiator caspase, often acting at the top of a proteolytic cascade that leads to the dismantling of the cell. It’s a molecular switch that can commit a cell to its own demise. The researchers found that CD8+ T cells deploy caspase-8 to directly control T. gondii infection within themselves.

To dissect this mechanism, the team conducted rigorous laboratory experiments using genetically modified mice. They compared mice whose T cells lacked caspase-8 with control mice whose T cells produced the enzyme normally. The results were stark and unequivocally demonstrated caspase-8’s critical role. Mice lacking caspase-8 in their T cells developed significantly higher levels of T. gondii in their brains compared to the control group. This outcome was particularly striking because both groups of mice mounted robust, seemingly strong overall immune responses against the infection. This suggests that merely having an "active" immune response isn’t enough; the quality and specific mechanisms of that response are paramount.

The difference in the health outcomes between the two groups of mice was even more dramatic. The control mice, with functional caspase-8 in their T cells, remained healthy and showed effective control over the parasite. In stark contrast, the mice without caspase-8 in their T cells became severely ill and, tragically, succumbed to the infection. Post-mortem examination of their brain tissue revealed a profound difference: the CD8+ T cells in these vulnerable mice were far more likely to be infected by T. gondii. This compelling evidence pointed to caspase-8 as a crucial intracellular guardian, limiting parasitic replication specifically within the very immune cells designed to fight it.

These findings not only illuminate a novel defense mechanism against T. gondii but also add substantial weight to the growing body of evidence that caspase-8 is broadly important in helping the body control a wide array of infectious threats. It underscores that the immune system’s arsenal extends beyond merely external elimination; it includes sophisticated internal controls within immune cells themselves.

The rarity of pathogens infecting T cells has long been a subject of scientific curiosity. Dr. Harris elaborated on this point, stating, "We scoured the scientific literature to find examples of pathogens infecting T cells. We found very few examples." This scarcity, she now believes, is no accident. "Now, we think we know why. Caspase-8 leads to T cell death. The only pathogens that can live in CD8+ T cells have developed ways to mess with Caspase-8 function. Prior to our study, we had no idea that Caspase-8 was so important for protecting the brain from Toxoplasma." This insight suggests an evolutionary arms race: pathogens that can infect T cells must have evolved sophisticated strategies to either neutralize or bypass caspase-8, or they would be swiftly eliminated. Toxoplasma, it appears, does infect T cells, but the T cells’ caspase-8 mechanism acts as a critical bottleneck, preventing widespread T cell infection and parasitic proliferation.

Broader Implications and Future Directions

This groundbreaking research holds profound implications for several areas of immunology and public health.

Firstly, for immunocompromised individuals, the findings provide a clearer molecular explanation for their vulnerability to toxoplasmosis. If their immune system is inherently weakened, or if the functionality of key components like caspase-8 is impaired, the critical self-destruct mechanism in T cells might not function optimally, allowing Toxoplasma to replicate unchecked within these vital immune cells. This understanding could pave the way for novel therapeutic strategies, perhaps by identifying drugs that can selectively boost caspase-8 activity or enhance T cell self-sacrifice in infected patients.

Secondly, the discovery significantly advances our understanding of brain immunology. The brain, long considered an "immune privileged" site, is now known to be under constant immune surveillance. Toxoplasma‘s ability to reside in the brain and its interaction with resident immune cells, including microglia and infiltrating T cells, is crucial for maintaining neurological health. Understanding the precise mechanisms of parasite control within the brain’s immune landscape could offer insights into other neuroinflammatory or neurodegenerative conditions where immune cell function is altered.

Thirdly, this work contributes to the broader field of host-pathogen interactions. It highlights the intricate and often surprising ways in which hosts defend themselves against intracellular pathogens. The concept of an immune cell sacrificing itself to eliminate an intracellular invader, rather than just destroying an external threat, adds a nuanced layer to our understanding of cellular immunity. This could inform research into other pathogens that infect immune cells, such as HIV or certain bacterial infections, where similar self-preservation or self-sacrifice mechanisms might be at play.

Future research building on these findings could explore several avenues. Scientists might investigate whether Toxoplasma attempts to actively inhibit caspase-8 in human T cells, and if so, how. Identifying the specific parasitic factors involved in T cell infection and the host factors that regulate caspase-8 activity could lead to the development of targeted therapies. Furthermore, examining the role of caspase-8 in other immune cell types that Toxoplasma infects could provide a more comprehensive picture of the body’s defense strategies. Ultimately, the goal is to translate these fundamental scientific discoveries into tangible benefits for patients, particularly those at highest risk of severe toxoplasmosis. This could involve developing new diagnostics to identify individuals with impaired caspase-8 function or designing immunomodulatory therapies that bolster this crucial defense pathway.

Study Details and Funding

The significant findings of this research were published in the prestigious scientific journal Science Advances, underscoring the rigorous methodology and impact of the work. The dedicated research team included Lydia A. Sibley, Maureen N. Cowan, Abigail G. Kelly, NaaDedee A. Amadi, Isaac W. Babcock, Sydney A. Labuzan, Michael A. Kovacs, Samantha J. Batista, John R. Lukens, and the lead investigator, Tajie Harris. The scientists transparently reported no financial conflicts of interest, ensuring the integrity of their findings.

The extensive and complex research was made possible through crucial financial support from a variety of esteemed institutions. Funding was primarily provided by the National Institutes of Health through multiple grants (R01NS112516, R01NS134747, R21NS12855, T32GM008715, T32AI007496, T32AI007046, T32NS115657, F30AI154740, T32AI007496, and T32GM007267). Additional vital support came from a University of Virginia Pinn Scholars Award, a UVA Shannon Fellowship, and UVA’s Strategic Investment Fund, highlighting the institutional commitment to pioneering research in immunology and neuroscience. This collaborative funding ecosystem is essential for enabling the kind of long-term, high-impact research that unravels fundamental biological mysteries and holds the promise of future clinical breakthroughs.