For decades, astrocytes, named for their star-like shape, have been recognized primarily for their supportive functions within the brain and spinal cord. They maintain the blood-brain barrier, regulate neurotransmitter levels, provide metabolic support to neurons, and contribute to synaptic function. However, their active participation in orchestrating a systemic repair response from afar following acute injury or chronic disease has largely remained elusive—until now.

"Astrocytes are critical responders to disease and disorders of the central nervous system—the brain and spinal cord," explained neuroscientist Joshua Burda, PhD, assistant professor of Biomedical Sciences and Neurology at Cedars-Sinai and the senior author of the seminal study. "We discovered that astrocytes far from the site of an injury actually help drive spinal cord repair. Our research also uncovered a novel mechanism used by these unique astrocytes to signal the immune system to clean up debris resulting from the injury, which is a critical step in the tissue-healing process." This revelation fundamentally shifts our understanding of CNS repair, moving beyond a localized damage control perspective to one involving a coordinated, region-wide effort initiated by these previously underestimated cells.

The research team has aptly named these newly identified cells "lesion-remote astrocytes," or LRAs, to distinguish their unique function and anatomical positioning relative to the injury site. They further identified several distinct subtypes of LRAs, indicating a complex division of labor among these critical responders. For the first time, this study meticulously details how one particular LRA subtype possesses the remarkable ability to detect damage from a significant distance and respond in ways that actively support recovery, effectively acting as long-range repair coordinators.

Understanding the Spinal Cord’s Vulnerability to Injury

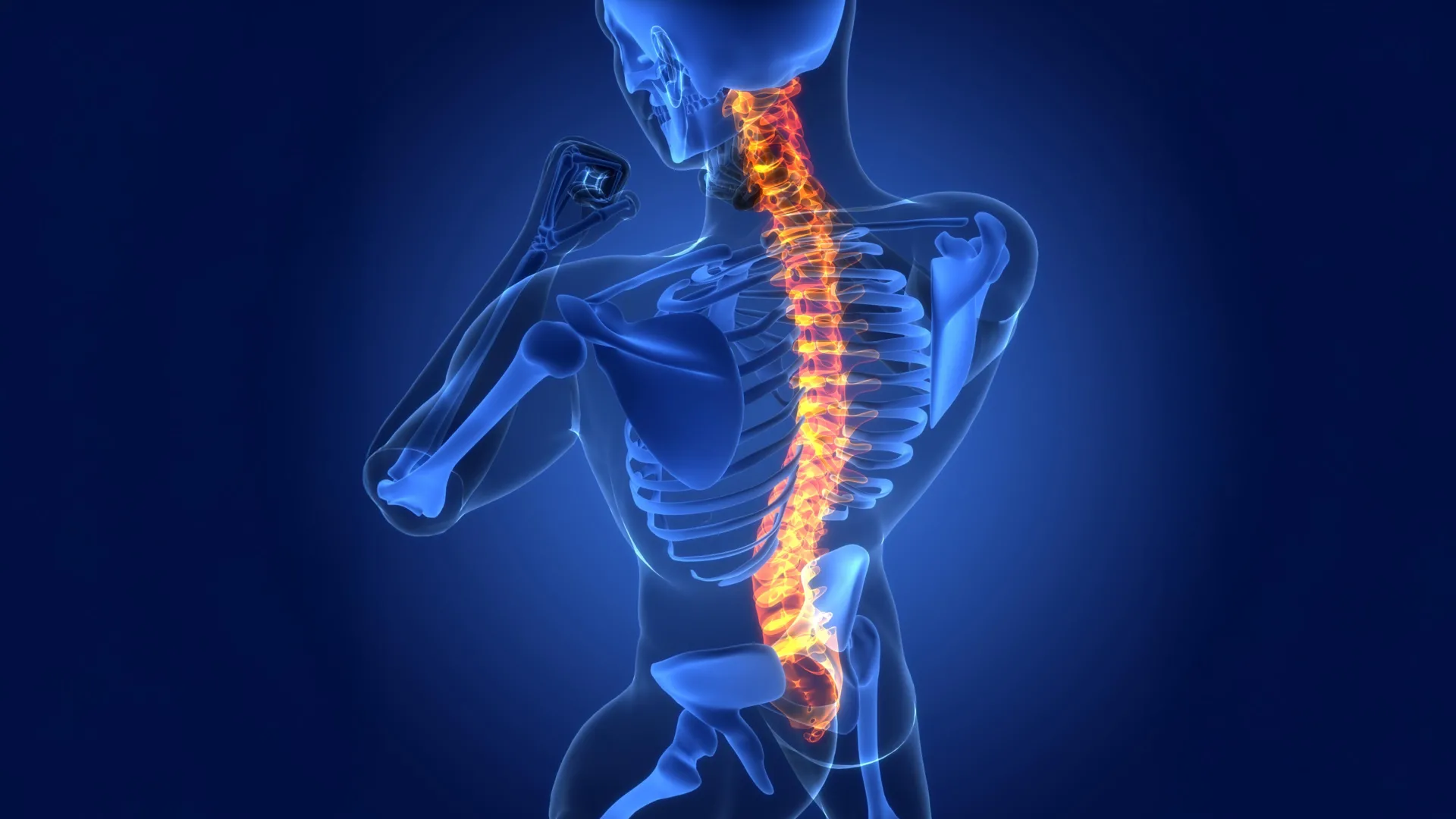

The spinal cord, a vital bundle of nerve tissue extending from the brain down the back, serves as the primary communication highway between the brain and the rest of the body. Its intricate structure comprises an inner region, the gray matter, rich in nerve cell bodies and astrocytes, surrounded by the white matter, composed of astrocytes and long nerve fibers (axons) encased in myelin. These fibers are responsible for transmitting sensory information to the brain and motor commands from the brain, enabling movement, sensation, and autonomic functions. Astrocytes are crucial in maintaining the delicate homeostasis required for these signals to travel efficiently and accurately.

When the spinal cord suffers a traumatic injury, such as from a fall, car accident, or sports injury, nerve fibers are often violently torn apart. This catastrophic damage can lead to a cascade of events, including immediate cell death, hemorrhage, inflammation, and the breakdown of myelin and neuronal components into cellular debris. The clinical consequences are devastating, frequently resulting in partial or complete paralysis below the injury site, loss of sensation (e.g., touch, temperature, pain), and disruption of bladder, bowel, and sexual function. Spinal cord injuries (SCIs) affect hundreds of thousands globally each year, imposing immense personal, social, and economic burdens, with current treatments largely focusing on stabilization and rehabilitation rather than significant functional restoration.

A particularly challenging aspect of SCI is the secondary injury cascade. Unlike many peripheral tissues where inflammation remains largely confined to the immediate injury site, the CNS, with its long nerve fibers, experiences a spread of damage and inflammation far beyond the original trauma. This diffuse inflammation exacerbates tissue destruction, creating an environment inhospitable to regeneration. Moreover, the fragmented nerve fibers break down into debris, particularly fatty myelin debris, which, if not effectively cleared, can impede axonal regrowth and exacerbate chronic inflammation, forming a persistent barrier to recovery.

The Orchestrated Cleanup: Lesion-Remote Astrocytes and Immune Signaling

Through a series of sophisticated experiments primarily involving mouse models of spinal cord injury, the Cedars-Sinai researchers meticulously demonstrated the pivotal role of LRAs in promoting repair. Crucially, their investigations also uncovered strong indications that this identical repair process manifests in spinal cord tissue samples obtained from human patients, significantly bolstering the translational potential of their findings. This cross-species validation is a critical step in bridging basic science discoveries to clinical applications.

The team’s detailed analysis revealed that one specific subtype of LRA produces a protein called CCN1 (Cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61). This molecule acts as a critical signaling agent, dispatching instructions to immune cells known as microglia. Microglia are the resident macrophages of the CNS, serving as the primary immune defense and cellular scavengers. In a healthy brain, they are constantly surveying their environment, ready to respond to pathogens or damage.

"One function of microglia is to serve as chief garbage collectors in the central nervous system," Burda elucidated. "After tissue damage, they eat up pieces of nerve fiber debris—which are very fatty and can cause them to get a kind of indigestion. Our experiments showed that astrocyte CCN1 signals the microglia to change their metabolism so they can better digest all that fat." This analogy of "indigestion" vividly captures the challenge microglia face when confronted with large amounts of lipid-rich myelin debris. Without proper metabolic reprogramming, their phagocytic capacity can become overwhelmed, leading to inefficient clearance and the persistence of inflammatory stimuli.

This improved debris removal, orchestrated by CCN1, may be a key factor explaining why some patients experience partial, spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury. The body’s intrinsic, albeit limited, repair mechanisms are likely benefiting from this astrocyte-mediated cleanup. To confirm the importance of this pathway, the researchers conducted experiments where they genetically eliminated astrocyte-derived CCN1. The results were stark: healing was significantly reduced.

Burda elaborated on the detrimental effects of CCN1 absence: "If we remove astrocyte CCN1, the microglia eat, but they don’t digest. They call in more microglia, which also eat but don’t digest. Big clusters of debris-filled microglia form, heightening inflammation up and down the spinal cord. And when that happens, the tissue doesn’t repair as well." This vicious cycle of ineffective phagocytosis leading to microglial accumulation and chronic inflammation highlights the critical necessity of efficient debris clearance for successful neurological recovery. The presence of undigested debris creates a persistent inflammatory milieu, inhibiting axonal regeneration and exacerbating neuronal loss.

Broad Implications for Neurological Diseases

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond acute spinal cord injury. When scientists meticulously examined spinal cord samples from human patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic autoimmune disease affecting the CNS, they observed the same CCN1-related repair process at play. MS is characterized by the immune system attacking the myelin sheath that insulates nerve fibers, leading to demyelination, axonal damage, and the accumulation of myelin debris. The ensuing chronic inflammation and impaired debris clearance contribute significantly to the progressive neurological deficits experienced by MS patients, including motor weakness, sensory disturbances, and cognitive impairment. The finding that LRAs and CCN1 are involved in MS suggests a fundamental repair pathway relevant to demyelinating diseases.

Burda emphasized that these basic repair principles, particularly regarding inflammation modulation and debris clearance, may apply broadly to a spectrum of injuries and diseases affecting either the brain or spinal cord. Conditions such as stroke, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and other neurodegenerative disorders also involve significant tissue damage, cellular debris, and an inflammatory response that can either aid or hinder recovery. For instance, in ischemic stroke, the sudden loss of blood flow leads to neuronal death and the generation of necrotic debris, which needs to be efficiently cleared to minimize secondary damage and facilitate tissue remodeling.

David Underhill, PhD, chair of the Department of Biomedical Sciences at Cedars-Sinai, underscored the profound significance of this work: "The role of astrocytes in central nervous system healing is remarkably understudied. This work strongly suggests that lesion-remote astrocytes offer a viable path for limiting chronic inflammation, enhancing functionally meaningful regeneration, and promoting neurological recovery after brain and spinal cord injury and in disease." His statement reflects a paradigm shift, recognizing astrocytes not just as passive bystanders but as active, long-distance orchestrators of CNS repair. This opens up entirely new avenues for therapeutic intervention that could target these remote cellular mechanisms.

Future Directions and Therapeutic Promise

Building on this foundational discovery, Dr. Burda and his team are now intensely focused on developing innovative strategies that can harness the CCN1 pathway to significantly improve spinal cord healing. This could involve several therapeutic approaches, including:

- Gene therapy: Delivering genes that enhance CCN1 production by LRAs.

- Pharmacological modulation: Developing small molecules that mimic CCN1’s effects or enhance its signaling pathway.

- Cell-based therapies: Potentially using modified astrocytes or their secreted factors to promote repair.

Beyond acute injury, the team is also delving into how astrocyte CCN1 may influence inflammatory neurodegenerative diseases and the aging process. As the brain ages, there is a natural increase in chronic low-grade inflammation, often referred to as "inflammaging," and an accumulation of cellular debris and dysfunctional proteins, which contribute to neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Understanding if and how LRAs and CCN1 play a role in managing inflammation and debris clearance in these contexts could open doors to novel interventions for age-related cognitive decline and neurodegeneration.

This monumental research was a highly collaborative effort, involving a large team of dedicated scientists from Cedars-Sinai and other institutions. Key additional Cedars-Sinai authors included Sarah McCallum, Keshav B. Suresh, Timothy S. Islam, Manish K. Tripathi, Ann W. Saustad, Oksana Shelest, Aditya Patil, David Lee, Brandon Kwon, Katherine Leitholf, Inga Yenokian, Sophia E. Shaka, Jasmine Plummer, Vinicius F. Calsavara, and Simon R.V. Knott. Other contributing authors were Connor H. Beveridge, Palak Manchandra, Caitlin E. Randolph, Gordon P. Meares, Ranjan Dutta, Riki Kawaguchi, and Gaurav Chopra.

The extensive funding for this complex and ambitious research underscores its importance and potential impact. Support was generously provided by numerous organizations, including the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Paralyzed Veterans Research Foundation of America, Wings for Life, the Cedars-Sinai Center for Neuroscience and Medicine Postdoctoral Fellowship, the American Academy of Neurology Neuroscience Research Fellowship, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine Postdoctoral Scholarship, the United States Department of Defense USAMRAA, The Arnold O. Beckman Postdoctoral Fellowship, and The Purdue University Center for Cancer Research. This collective investment highlights the urgent global need for breakthroughs in treating neurological injuries and diseases, and the Cedars-Sinai team’s discovery of lesion-remote astrocytes and the CCN1 pathway represents a significant leap forward in addressing this critical challenge.