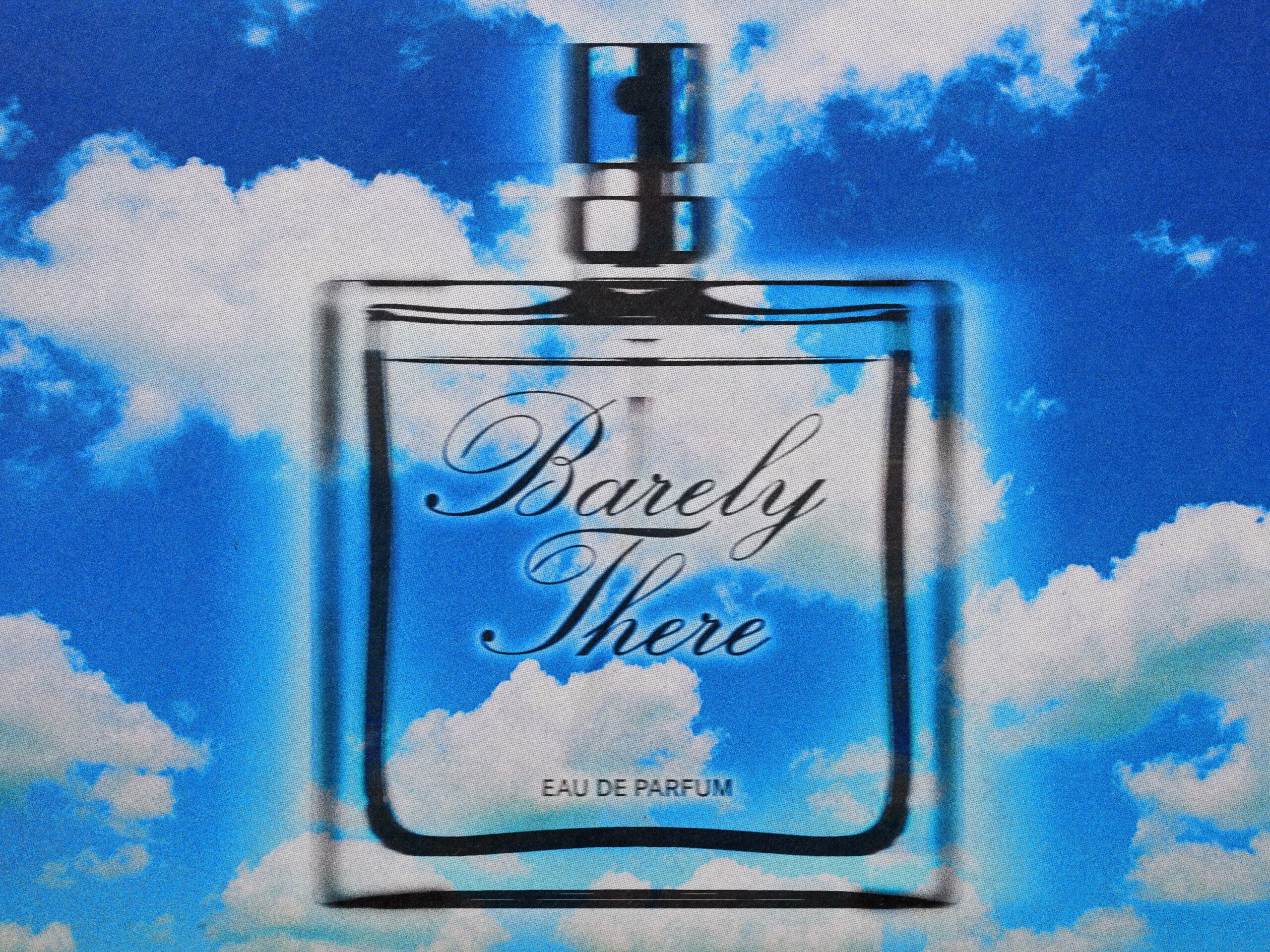

However, a profound seismic shift is occurring in the world of high-end perfumery. The most coveted scents of the current era are doing the exact opposite of their predecessors: they are retreating. We are witnessing the rise of the "anti-fragrance," a category of minimalist, genderless, and often synthetic-heavy scents designed to smell like nothing in particular, or perhaps more accurately, like a better version of the person wearing them. These are fragrances that whisper rather than shout, prioritizing an intimate "aura" over a public broadcast.

In the last five years, the fragrance industry has pivoted toward a "skin-scent" revolution. Leading the charge are niche houses and avant-garde perfumers who have traded exotic resins and heavy florals for notes that evoke the mundane and the familiar: cold morning air, the crispness of clean laundry, the mineral scent of a warm sidewalk after rain, or the subtle musk of skin just out of a shower. Fragrances like Byredo’s Blanche, DS & Durga’s Notorious Oud, and the viral sensation Paper from Commodity represent this new guard. They are nearly imperceptible to the casual passerby, requiring the proximity of a hug or a leaned-in secret to be fully realized. This shift reflects a broader cultural movement where fragrance is viewed less as a decorative accessory and more as a personal psychological tool—a "vibe" that exists for the wearer’s own comfort.

Christina Loft, a prominent fragrance critic and author of the newsletter The Dry Down Diaries, suggests that this movement is rooted in a desire for emotional resonance. "Fragrance is all about emotion and how something makes us feel," Loft explains. "There is a real art in bottling familiarity. It is actually much more challenging to create a simple scent that smells like something we know instinctively, like the smell of a lightbulb heating up or a fresh ream of paper, than it is to layer a dozen heavy notes together." She points to Clue Perfumery’s Warm Bulb as a prime example of this technical wizardry, noting that such scents force us to appreciate the beauty in the simple, overlooked elements of daily life.

The historical context of this evolution is essential to understanding its current momentum. For much of the 20th century, mainstream perfumery followed a rigid, hierarchical structure. Scents were built on a "perfume pyramid" consisting of top, middle, and base notes that unfolded over several hours in a predictable arc. This structure was designed for longevity and instant recognizability. If you wore a "powerhouse" scent in 1985, you wanted it to stay exactly the same from the morning meeting to the late-night dinner. But as Geza Schoen, the Berlin-based maverick behind Escentric Molecules, points out, that predictability has become a form of sensory boredom for the modern consumer.

Schoen’s 2006 release, Molecule 01, was the herald of the anti-fragrance movement. Built entirely around a single synthetic molecule called Iso E Super, the fragrance was famously "invisible" to many wearers. It didn’t smell like perfume; it smelled like a vague, woody warmth that appeared and disappeared throughout the day. "People want individuality," Schoen says. "They want to stand out without shouting. Anti-perfumes feel personal and quietly rebellious—like an ‘if you know, you know’ handshake." By stripping away the traditional pyramid, Schoen proved that a fragrance could be revolutionary by being almost nothing at all.

This minimalist approach is also a triumph of modern chemistry. While traditional perfumery relies heavily on natural essential oils—which are complex, "rich," and often heavy—the anti-fragrance movement is powered by high-tech synthetics. Spyros Drosopoulos, the founder of the Rotterdam-based brand Baruti, explains that creating an "invisible" scent is a highly technical feat of engineering. "Essential oils are often too complex for this style of work," Drosopoulos notes. "You cannot make a minimalist, transparent scent using only naturals; they are simply too dense. Instead, we use precise molecules like Romandolide for soft musk, Ambroxan for a skin-like saltiness, or Javanol for a sheer sandalwood effect. These materials are diffusive and long-lasting, but they don’t ‘smell’ like a perfume. They create an aura."

Drosopoulos compares this evolution to the history of art. If traditional French perfumery is the lush, detailed realism of the Renaissance, then anti-perfume is Cubism or Minimalism. It is an abstraction of scent that removes the "clutter" of the natural world to focus on a singular, clean sensation.

This olfactory shift aligns perfectly with the broader aesthetic trends of "quiet luxury" and "stealth wealth." In an era where overt displays of branding and logos are increasingly seen as gauche, the discerning consumer is looking for subtle markers of taste. Autumne West, the national beauty director at Nordstrom, has observed this transition firsthand. "Quiet luxury in fragrance is about refinement and restraint," West says. She notes that brands like Le Labo, Jo Malone, and Dior’s Privée collection have found massive success by offering scents that feel like a second skin rather than a costume.

The post-pandemic landscape has further accelerated this trend. After years of isolation, the return to public spaces and offices has created a new kind of "scent etiquette." In a crowded workspace or a public transit commute, wearing a heavy, room-filling fragrance can be perceived as an intrusion. "People are taking up space again," West observes, "but they are doing it with more sensitivity toward others. The scent you wear is still a form of self-expression, but it’s now a quieter, more intimate one. It’s about who you are to yourself and those closest to you, not who you are to the entire room."

This intimacy is a recurring theme among the "Smell-tok" community on TikTok, where fragrance influencers have moved away from describing scents in terms of ingredients like "bergamot" or "patchouli," and instead describe them in terms of feelings or aesthetics. Influencers like Holli Robinson describe skin scents as "grounded," "calm," or "cozy." On these platforms, a fragrance isn’t just a smell; it’s a "main character energy" that remains hidden from everyone but the protagonist. Robinson argues that anti-fragrances resonate because they feel "authentic" and "non-performative." In a digital age where so much of our lives is curated for public consumption, a scent that only you can smell feels like a private sanctuary.

Furthermore, the rise of gender-neutral scents has dismantled the old marketing tropes of "For Him" and "For Her." The anti-fragrance, by its very nature, does not care about the gender binary. A smell that evokes "clean paper" or "salty skin" is inherently universal. Drosopoulos asserts that the binary thinking of the 20th century was always a marketing fabrication that has finally reached its expiry date. "People want scents that feel safe and authentic to their own identity, not a set of rules dictated by a board of directors," he says.

There is also a philosophical layer to this movement. In an era dominated by Artificial Intelligence and the digital replication of almost every human experience, scent remains one of the few things that cannot be digitized, copy-pasted, or generated by an algorithm. You cannot download a smell. By choosing a fragrance that is subtle, shifting, and reactive to one’s own skin chemistry, individuals are reclaiming a primal, analog form of humanity. It is a celebration of the physical self in an increasingly virtual world.

Ultimately, the popularity of the "whisper" scent suggests a collective cultural fatigue. We are overloaded with sensory data—notifications, bright screens, loud politics, and constant noise. In this context, a fragrance that smells like "nothing" is a form of relief. It is a palate cleanser for the soul. As Christina Loft puts it, "Some days you want to fill a room, and that’s fine. But more and more, we are seeing people build ‘fragrance wardrobes’ where they have the range to be quiet. There is a newfound power in being the person who doesn’t need to be heard to be felt."

The "cologne guy" may not be dead, but he has certainly evolved. He no longer arrives five minutes before he enters the room; now, he waits until you are close enough to notice the subtle, warm, and mysterious glow of a scent that belongs only to him. In the world of modern fragrance, the most profound statement is often the one made in total silence.